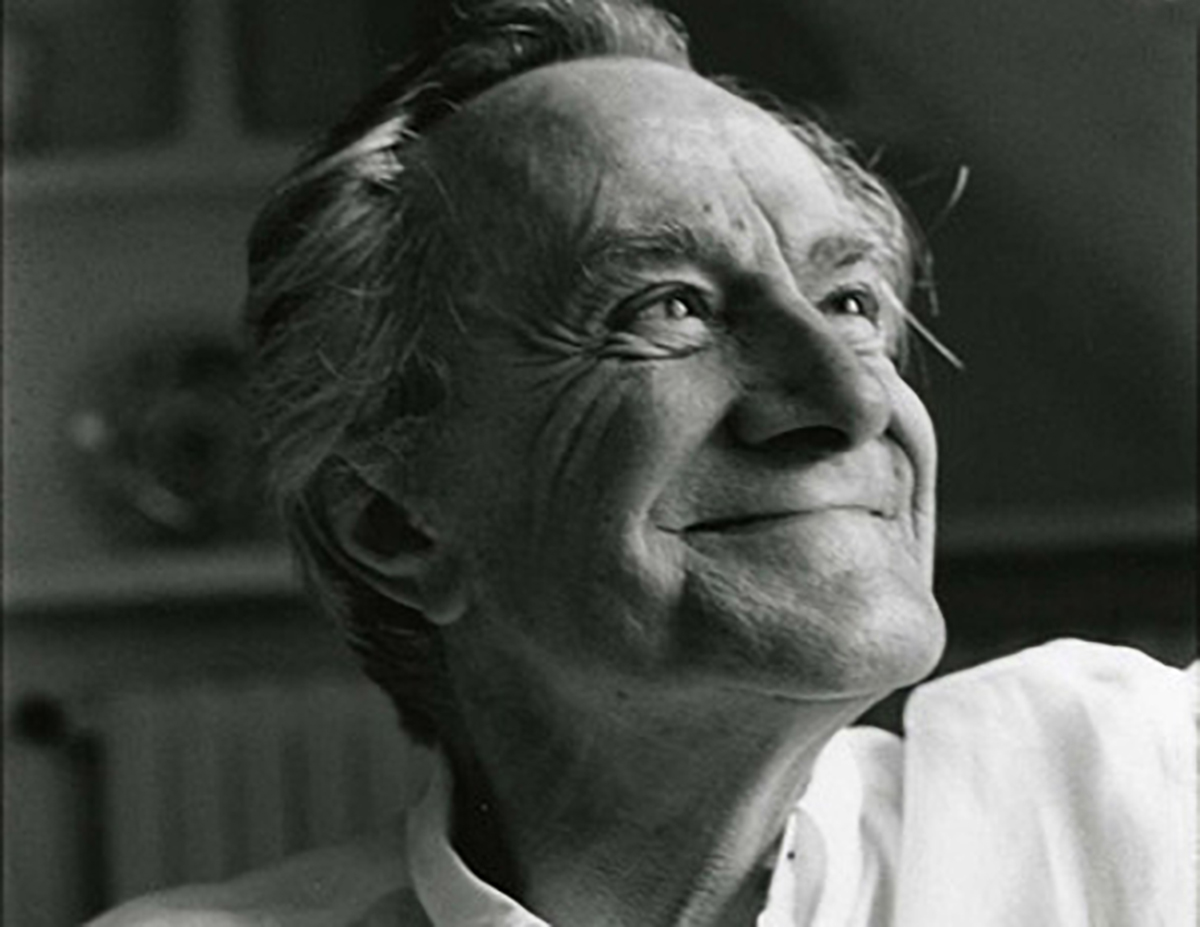

Jean-François Lyotard

Former Professor of Media Philosophy at The European Graduate School / EGS.

Biography

Jean-François Lyotard, Ph.D., (b. 1924 in Versailles) became one of the world’s foremost philosophers, noted for his analysis of the impact of postmodernity on the human condition. A key figure in contemporary French philosophy, his interdisciplinary discourse covers a wide variety of topics including knowledge and communication; the human body; modernist and postmodern art, literature, and music; film; time and memory; space, the city, and landscape; the sublime; and the relation between aesthetics and politics. At the time of his death in 1998, he was University Professor Emeritus of the University of Paris VIII, and Professor, Emory University, Atlanta. Former founding director, Collège International de Philosophie Paris, and Distinguished Professor at the University of California, Irvine, as well as Visiting Professor at Yale University, and other universities in the USA, Canada, South America, and Europe. Director of the exhibition ‘Les Immatériaux’, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

Author of The Postmodern Condition; Phenomenology; The Differend; Just Gaming; Peregrinations: Law, Form, Event; Heidegger and ‘The Jews’; The Inhuman; Libidinal Economy; Toward the Postmodern; Political Writings; Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime; Duchamp’s Transformers; Postmodern Moralities; Signed, Malraux.

Jean-François Lyotard was born 1924 in Versaille, France. Jean-François Lyotard became agrégé in philosophy in 1950 and received his Docteur ès lettres in 1971. After ten years of teaching philosophy in secondary schools (in Constantine, Algeria from 1950 to 1952), twenty years of teaching and research in higher education (Sorbonne, Nanterre, CNRS, Vincennes), and twelve years of theoretical and practical work devoted to the group ‘Socialisme ou barbarie’, and later for Pouvoir ouvrier, he taught philosophy at the University of Paris-VIII (Vincennes, Saint-Denis). Jean-François Lyotard was a council member and founding director at the Collège International de Philosophie, Paris, Professor Emeritus at the University of Paris, Visiting Professor at Yale University, and other universities in the USA, Canada, South America, and Europe, and was for several years Professor of Critical Theory at the University of California, Irvine. He moved from that position to Emory University in Atlanta, where he was Professor of French and Philosophy, and he was University Professor Emeritus of the University of Paris VIII. He was also director of the exhibition ‘Les Immatériaux’, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. He passed away in Paris during the night of April 20–21, 1998.

Jean-François Lyotard was a political activist along generally Marxist lines through the ’50s and ’60s until making a radical break with the tenets of Marxism while making the turn to postmodernism in the ’80s. His turn away from Marxism became an integral tendency of postmodernism in its rejection of totalizing and totalitarian modes of thought. Jean-François Lyotard’s truly innovative (or experiential) thinking – and certainly the thinking for which he has become renowned – is particularly exemplified in two books: The Postmodern Condition, and The Differend.

Jean-François Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (1979) is often said to represent the beginning of Postmodern thought. It was originally written for the Quebec government as an epistemological report. The text is an examination of late capitalist configurations of science, technology and knowledge. The status and function of ‘metanarratives’ is one of the principal foci of the book, in particular the way in which social and scientific configurations are legitimated by the teleological meanings formed by metanarratives. The historical materialist account of how society functions propounded by Marx, for example, gives meaning to dispersed social and scientific activities which they may not possess in themselves. The Enlightenment and German Idealism created powerful metanarratives which structured the production and use of knowledge during modernity. The metanarrative is a defining characteristic of modernity, around which modern society is structured and organized. Postmodernity implies that these goals of knowledge are now contested, and, furthermore, that no ultimate proof is available for settling disputes over these goals.

With the publication of his essay ‘Answering the Question: What is Postmodernism?’ in 1982, Jean-François Lyotard addresses the debate about the Enlightenment and specifically Jürgen Habermas’ take on the Enlightenment project. Jean-François Lyotard argues that all aspects of modern societies rely on ‘grand narratives’, or a sort of meta-theory that seeks to explain the belief system that exists. These metanarratives represent totalizing explanations of things like Christianity or Marxism – dominant modes of thought. For Jean-François Lyotard, the Enlightenment project as promoted by Jürgen Habermas constitutes another attempt at authoritative explanation. Thus, Jean-François Lyotard bases his definition of Postmodernism on the idea that postmodernist thought questions, critiques, and deconstructs metanarratives by observing that the move to create order or unity always creates disorder as well. Instead of ‘grand narratives’, which seek to explain all totalizing thought, Jean-François Lyotard calls for a series of mini-narratives that are ‘provisional, contingent, temporary, and relative’. Jean-François Lyotard, then, provides us with an argument for the postmodern breakdown or fragmentation of beliefs and values instead of Jürgen Habermas’ proposal for a society unified under a ‘grand narrative’.

In his work, Jean-François Lyotard has written of speculative discourse as a language game – a game with specific rules that can be analyzed in terms of the way statements could be linked to each other. The ‘differend’ is the name Jean-François Lyotard gives to the silencing of a player in a language game. It exists when there are no agreed procedures for what is different (be it an idea, an aesthetic principle, or a grievance) to be presented in the current domain of discourse. The differend marks the silence of an impossibility of phrasing an injustice. For Kant, the sublime feeling does not come from the object (e.g., nature), but is an index of a unique state of mind which recognizes its incapacity to find an object adequate to the sublime feeling. The sublime, like all sentiment, is a sign of this incapacity. As such the sublime becomes a sign of the differend understood as a pure sign. The philosopher’s task now is to search out such signs of the differend. A true historical event cannot be given expression by any existing genre of discourse; it thus challenges existing genres to make way for it. In other words, the historical event is an instance of the differend.

Unlike the homogenizing drive of speculative discourse, judgment allows the necessary heterogeneity of genres to remain. Judgment, then, is a way of recognizing the differend – Hegelian speculation, a way of obscuring it. The force of Jean-François Lyotard’s argument is in its capacity to highlight the impossibility of making a general idea identical to a specific real instance (i.e. to the referent of a cognitive phrase). Jean-François Lyotard’s thought in Le Différend (The Differend) (1983) is a valuable antidote to the totalitarian delirium for reducing everything to a single genre, thus stifling the differend. To stifle the differend is to stifle new ways of thinking and acting.

Jean-François Lyotard is best known to English speakers for his analysis of the impact of postmodernity on the human condition. A key figure in contemporary French philosophy, his interdisciplinary discourse covers a wide variety of topics including knowledge and communication; the human body; modern and postmodern art, literature, and music; film; time and memory; space, the city, and landscape; the sublime; and the relation between aesthetics and politics. Jean-François Lyotard maintained in The Differend that human discourses occur in any number of discrete and incommensurable realms, none of which is privileged to pass judgment on the success or value of any of the others. Thus, in Économie libidinale (Libidinal Economy) (1974), La Condition postmoderne: Rapport sur le savoir (The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge) (1979), and Au juste: Conversations (Just Gaming) (1979), Jean-François Lyotard attacked contemporary literary theories and encouraged experimental discourse unbounded by excessive concern for truth.

‘Let us wage a war on totality; let us be witness to the unrepresentable; let us activate the differences and save the honor of the name. Deconstruction is only the negation of the negation, it remains in the same sphere, it nourishes the same terrorist pretension to truth, that is to say the association of the sign – here in its decline, that’s the only difference – with intensity. It requires the same surgical tampering with words, the same split and the same exclusions that the lover’s demand exacts on skins.

‘The artist and the writer are working without rules in order to formulate the rules of what will have been done. Hence the fact that work and text have the character of an event; hence also, they always come too late for their author, or, what amounts to the same thing, their being put into work, their realization always begins too soon. Post modern would have to be understood according to the paradox of the future (post) anterior (modo).

‘The sublime feeling is neither moral universality nor aesthetic universalization, but is, rather, the destruction of one by the other in the violence of their differend. This differend cannot demand, even subjectively, to be communicated to all thought.’ – (Jean-François Lyotard)